What I have here are two novels that I read three months ago -- I liked them both at the time (though I'm pretty sure I had some reservations and criticisms), but, at this point, what I can say about them will be pretty vague and general. So I'm slamming the two of them together into one post in hopes that two mediocre reviews will be nearly as good as one focused one. Arguments, complaints, counter-examples, and any other commentary is always welcome; the comments are open.

Case Histories by Kate Atkinson

by Kate AtkinsonThis is the first of what unexpectedly turned into a series of detective novels; Atkinson had previously written three standalone novels (one of which,

Behind the Scenes at the Museum, had won the Whitbread Award) and a collection of short fiction, and so

Case Histories looked, when it was published, like a literary novel with elements of mystery in it rather than "a mystery novel."

And the storytelling in

Case Histories is very much on the literary side -- the first three chapters set up three parallel stories in 1970, 1994, and 1979, each titled "Case History" (Numbers 1, 2, and 3), before getting to our detective, Jackson Brodie, with the fourth chapter, and then rotate among several viewpoints from those three cases until all of the mysteries are revealed and solved (not really by Brodie) in the end. Brodie is a private detective (ex-police, ex-soldier), hired to solve problems, but, of course, the cliche in detective novels is that the PI isn't supposed to solve murders but does anyway. Atkinson doesn't follow the cliche; one of Brodie's cases is looking into a death, but he's nothing like the standard mystery-novel PI.

I'm not sure

why the mystery audience has taken Atkinson so much to heart -- I was introduced to

Case Histories by my then-colleague, who edited The Mystery Guild book club, and the subsequent three novels have all been picked up by mystery readers, so this is clearly happening -- from the evidence of

Case Histories; it really does take a literary novel's stance on murder and death, that they happen and are often inexplicable, and that they can't be "solved" or explained in the way that most mystery books try to do. Still, I'm not about to tell other people what they like best about their own genre:

Case Histories is an incisive novel that is very smart about people and what they do to one another, and clearly Brodie is a deeply appealing main character. (Though he's not as central to this book, either as the focus of action or as a Ross Macdonald-esque focus of attention, as one might expect.)

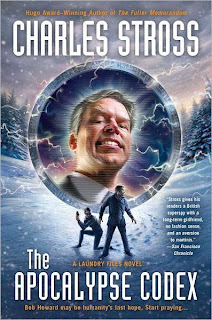

Rule 34 by Charles Stross

by Charles StrossYou're reading this on the Internet, so I presume that you recognize the title's reference: if you can think of it, someone else has already made porn about it. Stross's novel

Rule 34 is not about porn directly, but it is about the Internet, about the connections and appropriations made there, and about -- as Bruce Sterling once put it, the uses that the street finds for other people's things.

Rule 34 is a near-future thriller -- more of a detective novel than

Case Histories is, actually, with a deep attention to what policing may look like very soon -- and a loose sequel to Stross's 2007 novel

Halting State (which

I reviewed here, glancingly, at the time).

It's also a surprisingly

wearying novel, one that works hard to prove to its audience that it's as up-to-the-minute as it can be, with its three-stranded second-person narration, its plethora of extrapolated detail about day-to-day life two or three tech generations down the line, and its fears about what computers, computer-aided technology and the society they're embedded in might allow before too long. As usual with Stross,

Rule 34 will fill the reader up to her eyeballs with ideas and concepts, but, unlike Stross's best books, I

felt filled up by

Rule 34. There's a kind of SF that feels driven by the need to be utterly up-to-date, to be the new model everything, and

Rule 34 gives off that aura: this is SF as cutting-edge as Stross can make it, about everything that he can think of or crowd-source, about the Way We Will Live in a decade or so in all its terror and wonder.

I personally find that Stross can be a bit dour and pessimistic the closer he tries to hew to realistic futures and technological extrapolation, either because the sheer scale of the effort daunts him or because the portents of that looming future are that frightening. (Oddly, his books about the imminently

looming Lovecraftian apocalypse -- the novels about the secret British organization called the Laundry that begin with

The Atrocity Archives -- feel brighter and

less doom-laden to me, perhaps because of sheer whistling-past-the-graveyard bravado.) I respected

Rule 34, and was awed by it, but I don't think I can quite say I

loved it. But Stross is one of only a handful of writers even

trying to seriously grapple with what daily life might look like ten or twenty years from now, and

Rule 34 is perhaps his strongest attempt in that direction: it is likely to be proven right in a dozen major ways and a thousand minor ones.

This was the month I decided to get serious about catching up on my reviews, and so I'm all caught up as this posts...right? (Note: I'm writing this on July 22nd, with 26 books in various piles on my desk, waiting for me to blather about them. I'll leave this part in, and note at the end how well I actually did.)

This was the month I decided to get serious about catching up on my reviews, and so I'm all caught up as this posts...right? (Note: I'm writing this on July 22nd, with 26 books in various piles on my desk, waiting for me to blather about them. I'll leave this part in, and note at the end how well I actually did.)